Adam Galinsky has spent his career getting inside the heads of business professionals. As Paul Calello Professor of Leadership and Ethics and chair of the Columbia Business School Management Division, he is uniquely qualified for his vocation. In over 200 published pieces and a best-selling book (Friend & Foe: When to Cooperate, When to Compete, and How to Succeed at Both), Galinsky has probed the conscious and unconscious drivers of leadership and business success.

At various junctures in his career, Galinsky has focused his research on perspective-taking, which is the act of assuming another’s point of view. What is perspective-taking, and how can it make you a more effective leader? In Friend & Foe, Galinsky devotes an entire chapter — entitled “Seeing It Their Way to Get Your Way” — to the subject. This article reviews the content of that chapter to provide a preview of the types of insights you’ll gain from studying at the Columbia Business School Executive Education Advanced Management Program. Galinsky is just one of the many world-class experts you’ll encounter when you enroll.

What Is Perspective-Taking?

According to Friend & Foe (p. 59), perspective-taking is “the ability to see the world from the perspective of others.” Galinsky identifies this leadership skill as a “critical ingredient for managing both our friends and our foes.”

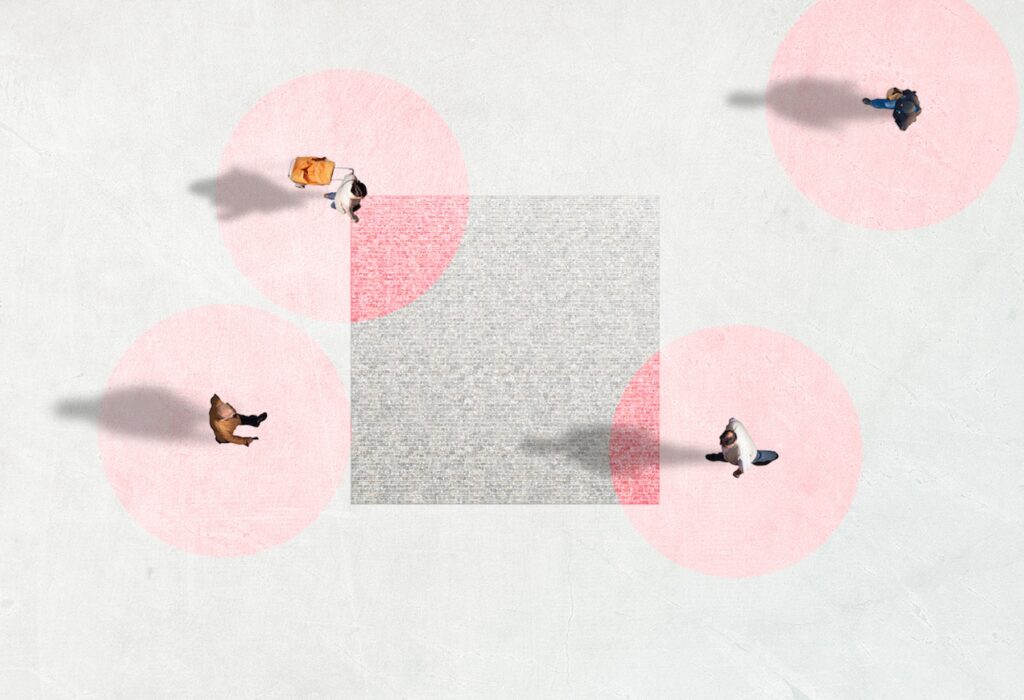

Perspective-taking is a critical skill for leaders, but it’s one that they often lose as they ascend the ranks. That’s because “power reduces the ability to understand how others see, think, and feel.” That description makes perspective-taking sound a lot like empathy; the two are related, but with a crucial difference. Perspective-taking involves understanding another’s point of view and emotions, while empathy requires feeling another’s emotions. Empathy can push you toward compassion, an essential human trait but one that’s not always beneficial in business.

“At just the right level, mimicry becomes an effective negotiating tactic, putting your negotiating partner more at ease with you and more amenable to concessions.”

Perspective-taking enables you to expand your options in resolving conflicts and overcoming leadership challenges. In negotiations, for example, perspective-takers can “expand the pie” by understanding their negotiating partners’ priorities. This can broaden the range of concessions and compensations on the table (e.g., by realizing something previously undervalued is, in fact, very valuable to one party). The end result is a win-win.

Just in case this leaves you with the sense that Galinsky’s research is all about touchy-feely moments, it should be noted that his other experiments have investigated the benefits of projecting power and the efficacy of workplace sarcasm in promoting creativity. Galinsky’s focus is always on results.

Perspective-Taking in Negotiations

“To succeed in a negotiation, it helps to understand where the other party is coming from,” Galinsky explains in Friend & Foe (p. 212). Naturally, you need a firm grasp on your needs and priorities to bargain. Understanding your partner’s needs is just as important, however.

To illustrate, Galinsky cites an incident from the 1912 presidential election. Theodore Roosevelt’s campaign printed up millions of promotional fliers without first licensing a copyrighted image it included. Stuck with a huge sunk cost, the campaign faced the possibility that it would have to pay a significant licensing fee. Fortunately for them, the licensor was not aware of the situation. When the campaign learned that he was eager to be associated with the Roosevelt campaign, it offered to include his image in an “upcoming” publication for a small fee. By understanding what the licensor valued (and, admittedly, by concealing crucial information), the campaign turned a potential financial catastrophe into a win.

Perspective-taking has a surprising physical manifestation: mimicry. Research shows that people respond positively to those who mirror or mimic their gestures, actions, and verbal idiosyncrasies, so long as the mimicry is subtle enough to go undetected. Perceptible mimicry can look like mockery, which, for obvious reasons, isn’t so effective a negotiating tactic. At just the right level, however, mimicry becomes an effective negotiating tactic, putting your negotiating partner more at ease with you and more amenable to concessions.

“Leaders face formidable challenges in adapting perspective-taking as a business tool.”

There are times when perspective-taking is counterproductive: for example, when the involved parties are adversaries. During the 1978 peace negotiations between Israel and Egypt, the principals — Menachim Begin of Israel and Anwar Sadat of Egypt — were highly suspicious of each other. Any efforts they made toward perspective-taking invariably resulted in their assuming the worst about the other. They grew so convinced of each other’s duplicitousness and chicanery that United States President Jimmy Carter, who was brokering the deal, realized he could only negotiate a settlement by separating the two and acting as a go-between.

Perspective-Taking and Competition Neglect

Entrepreneurs often make the critical error of focusing too much on themselves and their talents and not enough on customers’ needs or opportunities in the business environment. Take, for example, the person who decides to launch an Italian restaurant because they love the cuisine. They often forget to ask the critical perspective-taking questions:

- Will consumers love their take on Italian cuisine?

- Is there sufficient demand for Italian cuisine to support the business?

- Can they deliver restaurant meals at a competitive price?

By focusing on their dream — “I always wanted to have my own restaurant” — and neglecting the perspectives of potential customers, competitors, and suppliers, these entrepreneurs practically ensure failure. Does that sound overly harsh? In fact, 80 percent of entrepreneurs fail within 18 months of startup. In the restaurant business, 60 percent fail in the first year, and 80 percent last fewer than five years. As Galinsky notes in Friends & Foes, “This perspective-taking problem is so common that it has its own name: competition neglect.”

Online auctions demonstrate the principle. Most sellers choose to end their auctions between 5 and 9 p.m. They assume that this will optimize their return since that’s when site traffic is highest. This rationale fails to take into account relative demand. Traffic is high during these hours, but so is the number of auctions drawing to a close. In fact, relative demand is higher at 2 a.m. That’s because so few auctions close at that hour. Studies show that profits for sales at that hour are measurably higher.

Perspective-Taking and Management

Leaders face formidable challenges in adapting perspective-taking as a business tool. Their authority roles obstruct access to their subordinates’ concerns and ideas; because they spend so much of their time in the c-suite, senior executives must make a concerted effort to interact with managers and others to hear what they are thinking. Even then, many employees are understandably reluctant to share suggestions with supervisors. They fear revealing their own shortcomings or provoking disagreements.

In the final analysis, the rewards are more than worth the required effort. Leaders benefit from perspective-taking in the following ways:

- Seeking input from others exposes you to new and potentially valuable ideas

- Seeking input from others also makes your subordinates feel valued and respected, which in turn promotes loyalty and a commitment to harder and more effective work

- Seeking input is a great way to secure buy-in: by involving others in the process, you get them invested in the outcome and promote a cooperative atmosphere that opens them to your solutions

Perspective-taking also helps business leaders understand the necessity to keep subordinates informed. Consider a scenario in which a boss tells a subordinate, “Drop by my office at 5 p.m. today, I have something we need to discuss,” without providing any additional information. That employee will likely spend the rest of the day nervously wondering whether they’re about to be admonished or worse, fired. In the end, it turns out to be a trivial matter, and the worry was for nothing — but the stress and lost productivity are no less real. Had the boss understood the employee’s perspective and consequent anxieties, they could have alleviated the situation by adding, “It’s no big deal, nothing to worry about” during initial contact.

The same principle holds true for emergencies. Studies show that people respond better to crises when they have a steady stream of information about the status of the emergency. Silence from leadership is often the worst way to manage a crisis, from subordinates’ perspective.

Discover Effective Management Insights Through Columbia Business School Executive Education’s Advanced Management Program

Perspective-taking is just one of the many concepts and strategies you’ll encounter in Columbia Business School Executive Education’s Advanced Management Program. The curriculum interweaves three themes — authentic leadership, strategic thinking, and dynamic execution — to spur innovative and effective leadership.

Over this rich 22-week learning experience, you’ll attend a blend of online and in-person sessions that include virtual workshops and lectures, in-person experiential learning modules, and independent assignments and reflections. Assessment tools and one-on-one executive coaching will help you develop self-awareness, analyze your strengths and weaknesses, and leverage personal values to become a more authentic leader. In lectures, seminars, and peer groups, you’ll explore the principles of value, strategic intuition, leading inclusively, psychological safety, decision-making processes, and negotiation. During the five-day immersion, you’ll apply strategic leadership techniques in unique experiential and team-building activities. By program’s end, you will have developed an action plan to address current challenges in your organization.

Your fellow participants will consist of fellow senior leaders, managers and executives with a minimum of 10 years of leadership experience. Program benefits continue long after the final session: Participants receive individualized career support, access to Columbia Business School’s global alumni network, and exclusive industry opportunities.

Visit the website to learn more. Convinced this is the right choice for you? Then start your application today. Choose from two start dates (one in February, one in September).